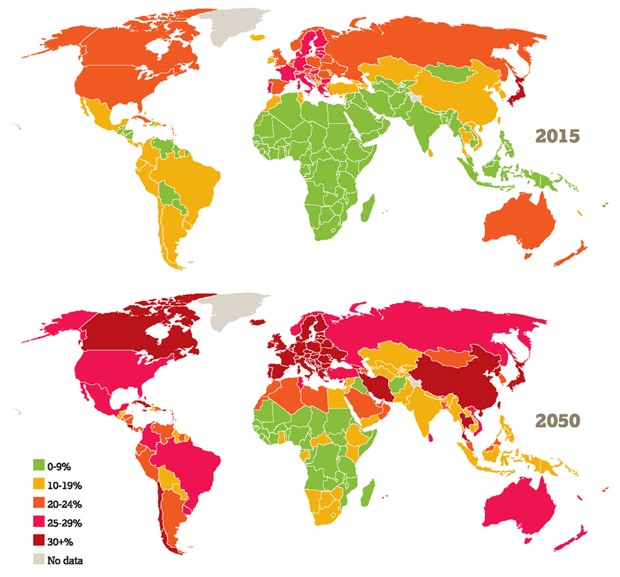

By 2100, the number of people aged 60 and over will reach 3.2 billion.

By the end of this century, the world is going to look a whole lot grayer: The proportion of people aged 60 and up is growing faster than any other age group.

Today, there are 901 million people aged 60 or above, making up just 12 percent of world’s population, according to the new Global AgeWatch Index Report from HelpAge International, a nonprofit that advocates for the rights of older people. But by 2100, the global population will reach 11.2 billion, and of that, 3.2 billion will be at least 60 years old, according to the latest report from the United Nations,. That’s more than triple the current numbers. In that time, the number of people aged 80 and over will also increase by more than seven-fold, from 125 million to 944 million.

It’s a phenomenon demographers commonly refer to as “population aging,” and it’s happening at an unprecedented rate as a result of longer life expectancy and lower fertility. Thanks in part to improvements made in global health—including significant strides in the fight against infectious diseases like HIV, malaria, and polio—people are living much longer. In fact, a studypublished last month in the journal Lancet found that, between 1990 and 2013, global life expectancy rose by more than six years, from 65.3 years to 71.5.

“The aging of the human population is a sign of success,” says John Wilmoth, director of the United Nations Population Division. “People live to much older ages, and the population is maintaining itself at a much lower mortality and fertility than we’ve experienced historically.”

Families are also getting smaller. Women on average will go from having two-and-a-half children to just two by 2100, and in some countries the fertility rate will be even lower. “It’s the background story to all of this,” Wilmoth says. “Many things came together to encourage people to have fewer births over their lifetime.”

Child-survival rates have dramatically increased, for example, meaning parents are no longer having several children so that one or two might survive. “At the same time, this happened when economies were becoming more industrialized, life was becoming more urban, work was becoming more disconnected from the home,” he adds, “so children become more difficult to manage.”

A rapidly aging population comes with its own economic and social challenges. Much of the overall population growth will happen in only a small handful of countries, predominantly inside the African continent. In Europe and East Asia, some countries’ populations will shrink after 2030 if the fertility rate remains low, which would mean fewer working adults to support social programs for the elderly.

The Lancet study also found that, though people are living longer, they’re also increasingly battling chronic illnesses like heart and respiratory diseases. That will leave some countries—particularly cash-strapped nations—scrambling to figure out how to pay for the aging population’s retirement and healthcare needs while dealing with a diminishing work force. Numbers from the Pew Research Center predict that Japan, which has the one of the fastest-aging populations, will have 72 elderly people (aged 65 or over) for every 100 working adults in 2050. South Korea is close behind, with 66 elders for every 100 working-age people.

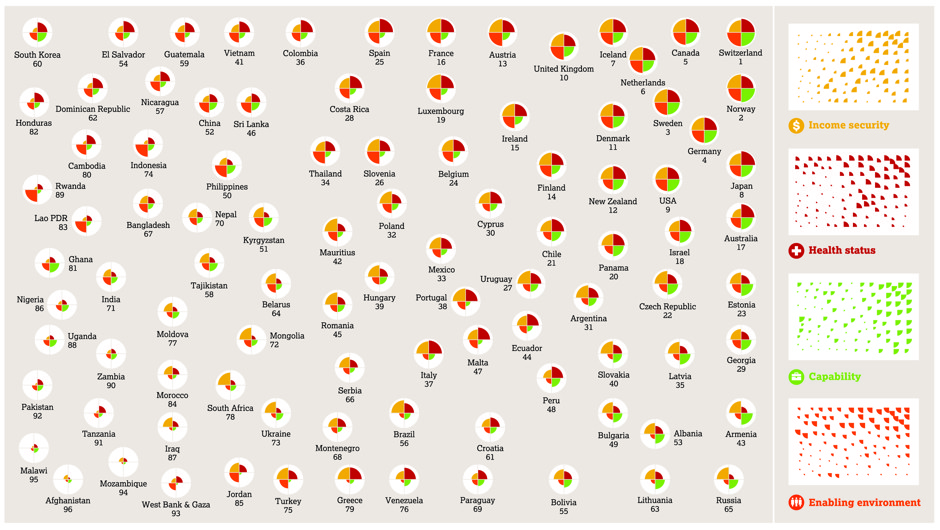

Yet not every country treats its elderly the same, according to the Global AgeWatch Index Report. It ranked 96 countries on the social and economic well-being of their 60-and-over populations. Countries like Switzerland, Norway, and Sweden scored the highest—meaning they, for the most part, provide adequate support for income security, health, employment, and educational opportunities for the elderly. In contrast, countries like Afghanistan, Malawi, and Mozambique ranked among the lowest.

Cities will also have to adapt. At least in the U.S., baby boomers—many of whom are now in their sixties and still very active—aren’t looking to move to a neatly carved-out retirement community away from the bustling city. “The old model is that you’d move into these active adult communities, away from where you spend most of your life, to a place where everybody is about the same age as you,” says Eran Ben-Joseph, head of the urban studies and planning department at MIT. “We see less and less of that.”

Rather, many prefer to “age in place,” or stay put in the same neighborhood they’re already in and build their own communities. But can cities accommodate their needs? As CityLab reported, virtually none of America’s cities or suburbs were built with the elderly population in mind, because back in the ‘60s, people didn’t typically live past 70 or 75. That means, for example, that older crosswalks may not give enough time an 80-year-old to slowly cross the street.

Urban developers will also have to take housing into consideration, says Ben-Joseph, as there is a gap between the supply and demand for homes that accommodate the elderly. “There are situations where people want to stay in the neighborhood but not necessarily in their old house, particularly if it’s too big,” he says. “But sometimes the supply of these particular developments in the cities have not been there.”

The concept of “aging in place” is starting to pick up in the U.S., but not as much in developing nations. “One of the things that worries us is that some of the developing nations are trying to replicate the U.S. model that we know is outdated,” Ben-Joseph says.

The good news is that the demographic shift will happen gradually—as long as fertility rates don’t become extremely low, says John Wilmoth at the United Nations Population Division. One solution is to encourage migration as a way to increase the younger population within a country. Another is to enhance support for families. “The critical thing is to somehow find ways to support couples and women who want to have babies and are also actively employed in the labor force,” he says. “Each country has a somewhat different situation in terms of how that plays out, and there is no magic bullet.”